The education white paper proposes the conversion of all schools in England to academies by 2022. If this takes place, the vast majority of schools affected will be primaries. Of the 15,343 mainstream schools that are not currently academies, 13,822 (90 per cent) are primary schools.

This is a massive change in the structure of the primary sector, with very little evidence of any benefits. The Education Select Committee report Academies and free schools stated in January 2015 that ‘there is at present no convincing evidence of the impact of academy status on attainment in primary schools’.

The Department for Education has carried out very little research on the subject, as Secretary of State Nicky Morgan confirmed in a letter to NUT Deputy General Secretary Kevin Courtney in April 2016:

We have not undertaken a ‘similar schools’ analysis for primary schools as, to date, there have been a relatively small number of schools with results for more than one academic year.

This prompts the question of why all primary schools should be forced to become academies when even the government admits that it lacks evidence to support its claim that the policy will produce school improvement. In fact there is growing evidence that it may do the opposite.

The one claim for primary school standards in the white paper is that:

2015 results show that primary sponsored academies open for two years have improved their results, on average, by 10 percentage points since opening, more than double the rate of improvement in local authority maintained schools over the same period.

This is an odd statement. It is not saying that all sponsored primaries perform better than the average. It is not even saying that sponsored primaries that have been open for two years or more perform better. It is only claiming that the specific subset of sponsored primaries that have been open for two years, and no more than two years, performed well.

The statement also compares two very different sets of schools. The results of sponsored academies tend to start from a lower base and so they have more room to grow. Many primary schools already have SAT results at 80 per cent or 90 per cent and so are unlikely to grow at the same pace.

The key question is whether a sponsored academy will improve more or less than a non-academy that starts from the same point in terms of results. Despite the Secretary of State’s claim, there is now a significant amount of data to enable us to explore that question, with 416 sponsored primaries having at least two years of SAT results.

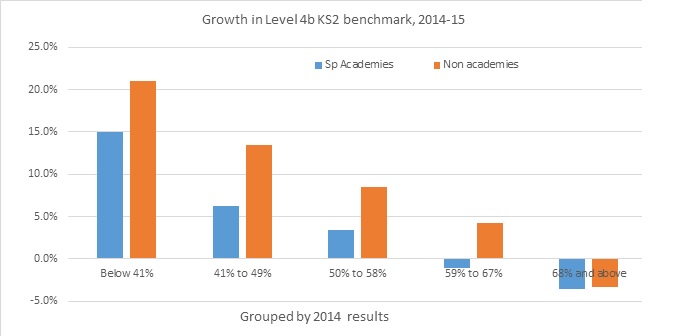

In December 2015, DfE released data showing SAT results, for 2015 and previous years, for every primary school in the country. This analysis is based on dividing sponsored academies into quintiles, or five equal groups, based on their prior year 2014 results. The growth from 2014 to 2015 has then been compared to local authority maintained schools with results in the same ranges.

The chart below is based on the new Level 4b benchmark but the results are the same if the old Level 4 benchmark is used, or if Level 5 is used. The first thing that is clear is that schools with a lower starting point in their 2014 results do indeed grow at a faster pace. Those with fewer than 41 per cent achieving a 4b in reading, writing and maths in 2014 saw their results grow on average over 15 per cent in one year. In contrast those with results between 59 per cent and 67 per cent grew at less than 5 per cent and those with results of 68 per cent or more actually saw their results, on average, fall.

However what is also clear is that, in each of the five comparisons, it was the maintained schools that grew at a faster pace. On average maintained schools increased their Level 4b SAT benchmark by 6.4 per cent more than similar sponsored academies. In a one form entry primary that is equivalent to two extra pupils achieving the benchmark.

The difference is very clear. Regression analysis shows that the data demonstrating that maintained schools perform better than similar sponsored academies is very robust, being statistically significant at the 99 per cent level.

This analysis is freely available for checking at http://bit.ly/KS2Regression.

The white paper has already come in for substantial criticism. As well as Labour and trade union opposition many Conservative MPs and local authorities have objected. Currently 84 per cent of primary schools are rated good or outstanding by Ofsted. It is not clear why the government feels the need to change a structure that seems to be working well.

Indeed the evidence indicates that the mass conversion of primary schools, as well as being extremely disruptive, could lead to a slower improvement in results. In 2014 Ofsted noted the difference between secondary and primary schools after the main period of academy conversion in the secondary sector:

Children in primary schools have a better chance than ever of attending an effective school. Eighty-two per cent of primary schools are now good or outstanding, which means that 190,000 more pupils are attending good or outstanding primary schools than last year. However, the picture is not as positive for secondary schools: only 71 per cent are good or outstanding, a figure that is no better than last year. Some 170,000 pupils are now in inadequate secondary schools compared with 100,000 two years ago. (Ofsted annual report 2014, 8)

Ofsted’s evidence on the disparity in standards between primary and secondary schools also featured in the CPRT blog on 15 April. On that basis, using secondary school results to support the drive to turn all primary schools into academies is hardly convincing.

The available evidence provides no justification for a policy of forced conversion of primary schools to academies. Indeed it suggests that it could lead to the same slowdown in improvement, with more students in schools rated ‘inadequate’, that has occurred in the secondary sector.

Henry Stewart is Co-founder of the Local Schools Network

henry@happy.co.uk

Readers may also wish to read Warwick Mansell’s recent blog on the government’s academies drive. His full-length CPRT report reviewing the evidence for the government’s structural changes will be published within the next few weeks.